S1 E23

WEEKLY NEWSLETTER FROM ANDREA BATILLA

MEN’S SPRING/SUMMER 2026 FASHION WEEK

This season (and the same will apply to the women’s shows in September), I decided to do something different—yet very simple.

What you’ll find here is a super-ranking of nearly every brand that showed or presented during the men’s fashion weeks.

As with any ranking, the brands are listed from best to worst—or rather, from the most meaningful to the least.

Any brands not listed here are, as the name suggests, out of competition.

1. Junya Watanabe

If there were such a thing as a fashion philosophy course, they should dedicate a full module to Junya Watanabe. When everything seems lost (as in this season of menswear shows), Watanabe reminds us not only that beautiful clothing is still possible, but that it must carry meaning—a narrative that makes sense. This collection began with a series of formal jackets made from upholstery fabrics and ended with a group of workwear-inspired jackets using the same materials. In between, it proposed a potential way to connect the opposing poles of the classic male wardrobe and the vast world of streetwear—one historically from the top down and the other from the very bottom up.

Junya is telling us that there are fundamental principles related to masculinity and its apparent immovability that cannot be avoided. But he’s also saying that right now, we’re in the midst of a complete reworking of those principles—calmly, piece by piece, without scaring anyone. The theme of the season—returning to a language that’s accessible to everyone—reaches its highest expression here.

Highlight: The jacquard sweater featuring a prairie house illustration, capable of bringing a smile even in dark moments.

2. Craig Green

Craig Green is one of the greatest talents in contemporary menswear. Strangely enough, no one has ever appointed him as a creative director—except Remo Ruffini, who involved him in the Moncler Genius project. A former student of Walter van Beirendonck, he inherited a graphic, childlike, naïve playfulness that he has transformed into fully realized collections, with a mature and thoughtful take on men’s wardrobes. This season—one of his most successful—he took another step toward something that’s notoriously difficult for British designers: commercial appeal.

Looking closely at Green’s work, it becomes clear how deeply he’s engaged with the living history of menswear, rendering it flexible and, in this case, finally understandable. Green has let go of excessive intellectualism and instead opened doorways that a modern man might actually walk through. If he does, on the other side he might find a colorful, slightly childish playground, where everything is accessible and fun. Green’s story is a joyful ode to being a man—and to leaving behind the burdens and mistakes of history.

Highlight: The over-the-top, expansive flower-power total look—cheerful, exaggerated, and pacifist.

3. Magliano

Watching Maglianic—the film directed by Thomas Hardiman in which Luca Magliano presented this collection—reminded me of something. Only now, after watching it again, do I realize what. It was the film Alessandro Michele made for his Spring 2016 pre-collection for Gucci, shot by Gia Coppola in New York, called The Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice.

In truth, the two films have nothing in common—except their precise visual articulation of the symbolic universe that defines a brand. Nearly a decade after Alessandro Michele’s explosive early collections, Magliano captures, with surgical precision, a world that’s shifting without a clear destination, filled with far fewer certainties.

It’s a journey full of absurd characters who say things that seem to make no sense, and whose stories we never fully learn. It’s a tale of exaggerated, hyperreal, character-driven personalities who are somehow adrift.

These are souls brought together by chance, building a universe of diversity, reflection, and empathy. Magliano’s world is chipped, scratched, faded, rusted—but through its cracks, it reveals a truth you won’t find anywhere else.

Highlight: The disheveled look of a Marxist philosophy professor at the village bar.

4. Sacai

Anyone looking for a truly surgical analysis of every piece in the male wardrobe should hop on a plane to Japan and visit Sacai and its founder, Chitose Abe. The Japanese were the first to rethink American streetwear and European formalwear back in the ’60s and ’70s. The same culture that, for example, produced the world’s best denim is what fuels Sacai.

One might wonder why Westerners rarely manage such a clear-eyed approach to a culture that is supposedly their own, while those far removed from Europe and the U.S. often do it so well. The answer lies in the Japanese design mindset, which is deeply intellectual and operates like that of an entomologist: study the subject, understand its principles, and then create a synthesis. It’s something Westerners struggle with—perhaps because they’re too close to both the material and the method.

In this simple and elegant collection, all the archetypes of menswear are represented and reworked. Just looking at it (let alone wearing it) feels refreshing and liberating. Chitose Abe has the gift of distilling centuries-old materials into a refined tale of the everyday. Even though it’s new, it has the symbolic weight of something that’s already a classic.

Highlight: The heavyweight cotton suit in collaboration with Carhartt—something we didn’t know we needed.

5. Dior Men

I wasn’t sure where to place Jonathan Anderson’s first show for Dior on this list. I watched it many times because something about it drew me in, while something else repelled me. Then it clicked.

The idea—most visible in the styling—of underdressing, of nonchalance, of everyday casualness, is genuinely interesting when applied to a brand like Dior.

Not trying too hard, not looking overly dressed, not wearing anything that screams new—these are the mantras of Anderson’s intellectual dandyism, which rejects full looks, logos, and instantly recognizable pieces as vulgar. Even the now-famous $200,000 coat looks like it’s made of ordinary tweed, not hand-embroidered with gold thread.

This is an attempt to escape the forced codes of contemporary menswear (including “quiet luxury”) and return to foundational principles that are so simple they’ve become out of reach.

That doesn’t mean Anderson, along with über-stylist Benjamin Bruno, has done something revolutionary. They’ve probably done the opposite. The effort here is one of visual detox—shifting focus back to the product, just as Watanabe did. In this rejection of excess lies a break from the dominant intellectualism and minimalism, both of which Anderson himself has explored at Loewe.

It’s a message few have understood, because this kind of mediocrity—or rather, everyday normalcy—has become something everyone wants to escape.

But maybe a beautiful striped shirt and an equally beautiful pair of jeans actually tell a much deeper story.

Highlight: The preppy good-boy look straight out of the 1980s.

6. Giorgio Armani

There’s a “before” and an “after” Giorgio Armani in the history of menswear—and now that everyone else is paying the price, that distinction is even more obvious.

Soft jackets that rest gently on the shoulders, light and roomy trousers, shimmering fabrics, invisible colors. It’s a visual language that Giorgio Armani popularized in the late ’70s and that today feels more relevant than ever—perhaps because it addresses the needs of a masculinity tired of centuries of pressure.

Armani’s wardrobe is inherently liberating. It lacks the stiffness of 19th-century uniforms and conveys a breezy, vacation-ready, subtly erotic mood—even when speaking of formal or work occasions.

It’s the perfect formula, though still far from being consciously adopted by many—perhaps because along with a linen suit, you might also need to buy a few rounds of therapy.

While we wait for the average man to accept that he can be something fluid, adaptable, and even a bit mysterious, we can lose ourselves in a film where being soft is a virtue, not a flaw.

Highlight: The timeless oversized suit.

7. Wales Bonner

Grace Wales Bonner belongs to that very small group of independent designers who have the talent to take over a major house, yet choose to remain autonomous. In today’s landscape, they’re like unidentified flying objects—likely with modest revenues—but they survive through a network of collaborations.

It doesn’t really make sense to compare these types of projects to luxury mega-brands; the financial gap is vast. Still, it’s worth noting that there is life outside LVMH and Kering—and it’s often more interesting.

Wales Bonner has a hyperreal way of portraying the everyday. She doesn’t aim for poetry, romanticism, or comforting endings. Her work is an honest snapshot of reality, free of pretension—echoing the same search for clarity we’ve seen in Watanabe and Dior.

Again, there’s little construction here, but a lot of sincerity. I’d even say honesty. And once again, there’s a reflection on the need to return to a comprehensible visual language—a way to re-engage with the culture of menswear, to reach those men still too afraid to change.

Highlight: The perfect-yet-imperfect tailcoat for unforgettable nights.

8. Hed Mayner

Hed Mayner is one of those lesser-known talents who, despite having a highly recognizable aesthetic, still manages to carve out space each season to add new elements to his visual language.

A poet of extreme oversized proportions, this season he too chose to simplify and pare back—likely in an effort to make his message more pointed. Many pieces are closer than usual to an everyday wardrobe, making them feel more believable. Others—especially the printed ones—are more abstract, retaining a fairy-tale quality that defines Mayner’s work.

Overall, this is yet another place where a significant rewriting of what men can or will have in their wardrobes is underway. A slow but steady expansion of outdated codes is happening—and thanks to designers like Mayner, those codes are starting to bend with the times.

Highlight: Jeans, white shirt, navy pullover, and trench—an ideal everyday uniform.

9. Niccolò Pasqualetti

Niccolò Pasqualetti’s first menswear show was deeply interesting. While his aesthetic still has some student-like or incomplete elements, Pasqualetti explores the idea of clothing with both great freedom and a deep sense of respect. Each piece is extremely complex in construction and materials, yet the overall impression is one of simplicity—at times, almost anonymity.

That word—anonymity—which might seem to stand in opposition to creativity, will become an essential ingredient in the coming years, as brands work to regain the trust of alienated consumers.

Of course, anonymity isn’t the first word that comes to mind when looking at Pasqualetti’s work—but within an independent, auteur-like vision of fashion, his message leans in that direction.

We’re in a moment of rejection—not of what’s new, but of what’s different—and many young designers are intentionally working at the edge between banality and creativity.

It’s a survival tactic, but also an exploration of long-ignored territories.

Highlight: The oversized aged-leather jacket as a reason to live.

10. Setchu

Satoshi Kuwata has stepped outside his comfort zone—one rooted in Japanese intellectualism—and let himself be swept into Central African culture, using it not just as inspiration but as a launchpad toward new, even physical, territories.

The blending of Zimbabwean craft with American utility wear, colonial references, and the bright colors of contemporary African fashion is a remarkably smart way to talk about non-Western cultures without plundering them or copying their sandals while ignoring their origins.

It’s also fascinating to see how a minimalist design approach can open up to color and embellishment without losing its roots. And equally striking is the fact that the notion of otherness is being represented by someone who, by birth, does not belong to Western culture—but knows it intimately.

Highlight: The colonial-style formal jacket over a neon pareo—redeeming what was once just bad styling.

11. Mordecai

Ludovico Bruno, the designer behind Mordecai, seems to live in an alternate reality where everything is gently pacified. Maybe he doesn’t like conflict—or maybe he’s had too much of it and wants to erase it. The result is a world with no sharp edges, no clashes, no aggression, no blaring volume, no violent behavior.

And yet, the root of his work comes from martial arts uniforms—specifically judo. This sport has a fascinating history tied to the fall of the shogunate, the banning of armed samurai, the arrival of Westerners in Japanese ports, and, more broadly, the transformation of a combat technique into one of peaceful defense. In Japanese, judo means “the gentle way.”

From all this, Bruno has created an aesthetic that speaks to men (and women) who keep their distance from traditional dress codes but still want to be seen. Maybe because they know their clothes are saying something different.

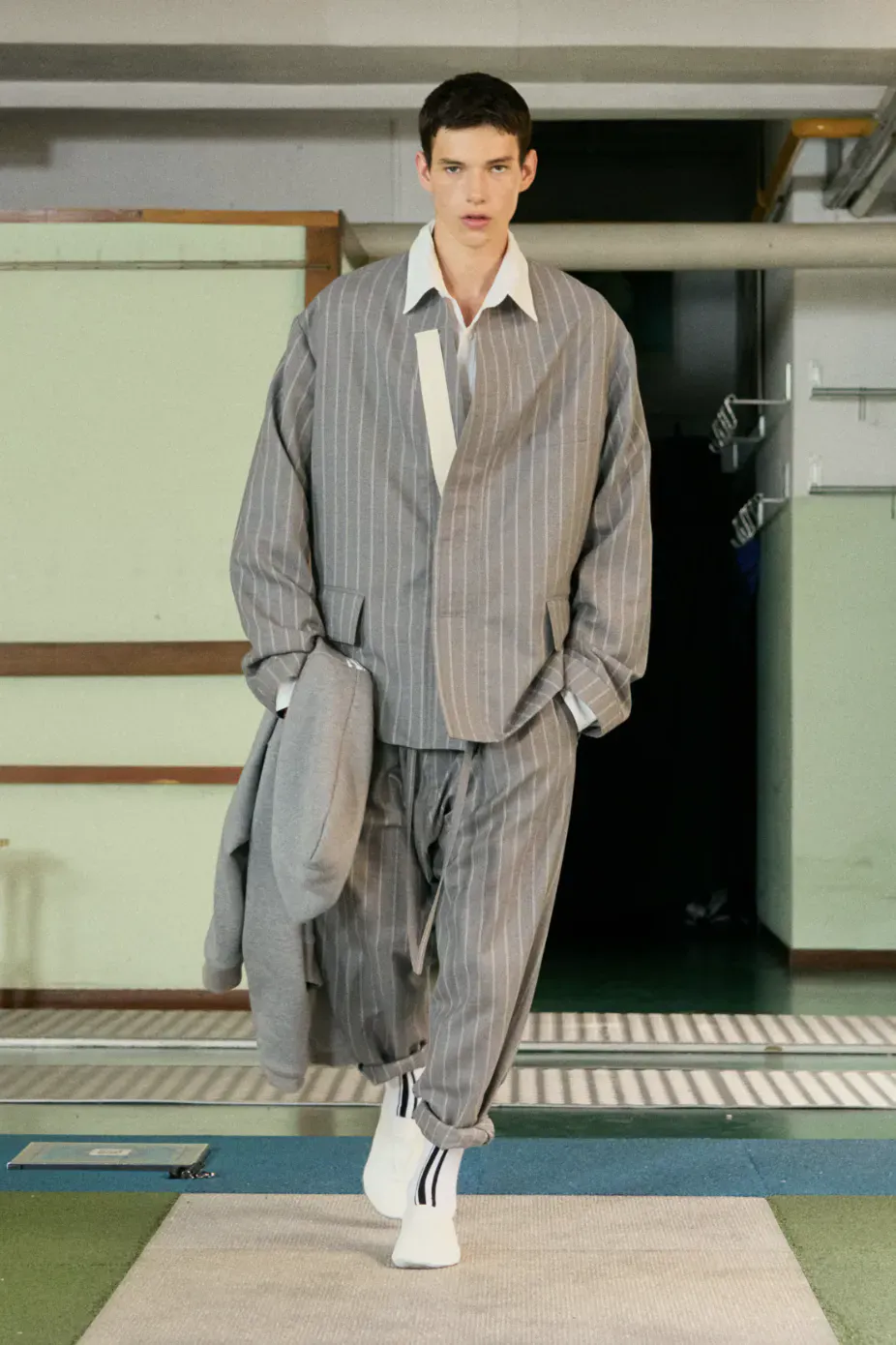

Highlight: The “pacified” pinstripe suit.

12. Saint Laurent

Anthony Vaccarello’s collection for Saint Laurent is probably the most beautiful of the season—but, as usual in his case, its relevance is very limited. Saint Laurent is a brand that sells huge-logo handbags to upper-middle-class women. But to find the quilted leather Loulou bag, you have to scroll way, way down the handbags section of the official website.

What Vaccarello and his partner in crime Francesca Bellettini prefer to do is create dreamy runway shows that the industry adores and that keep interest in the brand high. But this creates a split identity—two very distant realities—following an old marketing rule.

As we’ve seen, we’re in a moment that requires a strong dose of realism to win back the trust of both markets and consumers. Sure, that realism should involve more accessible pricing, but it mostly needs to come from greater attention to wearability, occasion, practicality, and real life.

At Saint Laurent, we are wonderfully far from real life.

Highlight: The amaranth suit for living in a transcendent dimension.

13. Martine Rose

Martine Rose is a detective of the everyday. She investigates what lies deep in the folds of clothing aesthetics. She studies how the neighborhood dealer dresses, or the undocumented immigrant, the young post office clerk, the aspiring soccer player. These are people who may never reach personal fulfillment—but who still manage to survive, precariously balanced at the margins of society.

Along with Grace Wales Bonner, she’s one of the very few female designers creating successful menswear collections. She was also the first to explore a strange mix of formalwear and active sportswear—a combination that eventually became one of the core aesthetics at Balenciaga, where she once worked.

The issue with Martine Rose is her lack of evolution. It’s hard to see how her message could grow to include broader meanings that go beyond just describing reality. Demna’s key move was to critique reality. Maybe Martine Rose should consider doing the same—from her own perspective.

Highlight: Active sportswear as a way of life.

14. Dolce & Gabbana

Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana are like living trend barometers. They sniff the air, observe, and then synthesize. That doesn’t mean they copy—but that they adjust to what’s working in the market while maintaining a specific style.

This collection of oversized pajamas, oddly enough, is out of sync with the general slowdown around the very idea of trends. So, when viewed after Dior, Vuitton, or Wales Bonner, for example, it feels disconnected from what’s happening—or about to happen.

Dolce & Gabbana’s collections reflect what people expect from an Italian brand: quality, moderate creativity, wearability, and a healthy dose of tactile and visual pleasure. All of this is softly projected into today’s trendscape.

This show followed that formula, but the brand’s identity came through a little too loudly—in the too-colorful pajamas, the too-oversized jackets, the overly bold stripes.

Right now, it’s as if brands need to disappear a little, to say less. That’s because sentiment toward luxury and its dynamics isn’t exactly positive.

Being immediately identifiable is now a deadly sin. It would be fascinating to see what Dolce & Gabbana could do with the idea of anonymity.

Highlight: The embroidered pajama—for when you really want to make a statement.

15. Dries Van Noten

Julian Klausner presented his first menswear collection as creative director of Dries Van Noten, following the founder’s departure. Klausner is clearly a fan of Miuccia Prada, Raf Simons, and Olivier Rizzo—the trio currently behind Prada. You can see it in the stripped-back styling, the slightly bruised color palette, and the faux-casual intellectual vibe. The show’s styling moved from the romantic Nancy Rohde to the much less romantic but more contemporary Robbie Spencer.

All of these elements, which everyone loved, have never been part of Dries Van Noten’s DNA. But Klausner had to start somewhere in order to make the brand his own—especially one still so closely associated with its founder.

My worry is that these kinds of moves often stem from a poorly managed coolness panic—a scramble to get back on the radar of “relevant” brands without a clear direction.

Dries has always been a bit on the fringe, promoting a poetic and decorative vision that many would now call outdated. Even during peak intellectualism, Van Noten was designing floral shirts and dresses, sending models down the runway past long banquet tables.

Finding your voice is hard—especially when the brand is still so recent. But Klausner may need to dig deeper if he wants to find the light.

Highlight: White shirt, khaki pants, and a massive pareo—a promising path.

16. Louis Vuitton

Pharrell has seriously dialed it down and decided to explore incredibly simple clothing. While this men’s collection was, in theory, inspired by a trip to India, in practice it marked a retreat—not only from streetwear and ornamentation—but from everything Virgil Abloh built, which now suddenly feels unsustainable.

The question is: why has that loud, symbolic world—so rooted in Black culture—suddenly gone out of fashion?

The answer lies in the difference between a designer and a creative director who just happened to land the job. A designer has an urgent need to tell stories and be heard. Often those stories are uncomfortable, and just as often, people aren’t paying attention. The at-large creative director, on the other hand, tries to position themselves right between commerce and edge—without upsetting anyone.

That’s what Pharrell has done and will continue to do. There’s nothing wrong with that—except that his predecessor was a revolutionary who’s deeply missed.

Highlight: The reproduction of the luggage Marc Jacobs designed in 2006 for The Darjeeling Limited by Wes Anderson.

17. Prada

Unfortunately, nothing seems to be working at Prada right now. I don’t know whether the Raf-Miuccia partnership is ending or if this is just a rough patch, but this collection showed a deep lack of meaning that left many puzzled.

Jonathan Anderson also worked on simplicity, ease, normalcy—but he put tremendous effort into not appearing intellectual or cerebral. Here, we’re still seeing a merino sweater worn over underwear, socks, and loafers. As unrealistic as it is already overdone.

In fact, everything that walked down the runway has already been seen.

The big question here: do Miuccia and Patrizio truly think it’s enough to just reissue what they’ve already done?

Or are they beginning to realize they’ll eventually have to say something new?

Highlight: The intellectual yachtsman’s weekend suit.

18. Kenzo

Nigo is a key figure in the history of streetwear, while Kenzo’s design director, Joshua Bullen, spent 11 years at Stone Island and later joined Givenchy with Matthew Williams. Together, they’re managing a brand that has lacked a reason to exist for quite some time.

The last spark of collective excitement came when the Opening Ceremony duo, Carol Lim and Humberto Leon, took over and made it appealing to a young audience—bringing back the brand’s 1980s heyday. But LVMH failed to capitalize on that moment—perhaps because, price-wise, Kenzo doesn’t qualify as luxury. It sits in a category the group doesn’t understand well: the “contemporary” mid-range.

That said, Kenzo is a mystery. The collections make no sense, but the project continues, like an appliance left running by accident—eventually overheating and breaking down.

Surely there are talented streetwear designers in the world, but none seem to be on anyone’s radar here—or worse, no one believes this kind of project has a future.

Highlight: The poppy-print shirt, the only surviving trace of Kenzo Takada’s legacy.

19. Rick Owens

When you decide to do a retrospective on your own work—a celebration of yourself—it often means you might not have anything new to say.

Rick Owens’s goth world is no longer a subculture—it’s an aesthetic so broad and elastic it now includes customers who probably don’t even know what goth is.

Lately, his runway performances have become repetitive, and his rebellious spirit seems stuck in a dull repetition of certain tropes. Maybe that’s normal. Maybe it’s even fair.

Still, from someone who built a dazzling career on subversion, we expect periodic reinvention. Instead, this time, Owens landed in a more commercial zone—and despite the pyrotechnic choreography, we saw surprisingly wearable clothes.

These are tough times for everyone, but if you strip Rick Owens of his edge and innovation, what’s left might just be nice clothes—hard to tell apart from other nice clothes.

Highlight: The all-black outfit that normalizes goth.

20. Comme des Garçons

For quite some time now, Rei Kawakubo’s collections have become little more than exquisite craftsmanship, with no storytelling behind them. Her myth—as icon, idol, and symbol of a creativity that once was and never will be again—lets her remain in a limbo where everyone pretends her work is still relevant. The truth is that since the ’90s, the very idea of creative exploration has radically changed. Designers now understand that it must have some commercial viability.

Thirty years ago, people actually walked around head-to-toe in Comme des Garçons—even in small-town Italy. Today, that’s no longer the case. People now use different codes to stand out.

What we’re seeing is fashion archaeology—executed with great care, but that’s where it ends. It no longer interacts with the present.

Comme des Garçons is now essentially a retail project called Dover Street Market, which sells mountains of Jacquemus and dozens of sub-brands like Shirt or Play—aimed at people who just need a heart logo on a T-shirt to feel stylish.

Rei Kawakubo is maintaining a project that has become curatorial. Maybe it’s time she steps aside and frees up the space she’s rightfully dominated since the ’80s—a space that could now foster talents who no longer need a mother figure.

Highlight: The perforated jacket—proof of a time long gone.

21. Willy Chavarria

Willy Chavarria has experienced explosive success in a short amount of time. Even though he’s 56 and has a long background as a design director at Calvin Klein, he’s been embraced as the only truly new thing to come out of New York in recent years.

His point of view is certainly interesting—not only because it doesn’t align with mainstream taste, but also because, like in this case, he delivers powerful political messages. The beginning of this show was a dramatization of how prisoners are treated when they’re about to be deported after entering the U.S. illegally.

It would all be quite powerful—if only that depth were visible in the clothes. They play the indie card but are actually quite reassuring. Being anti-establishment is hard work. You have to bleed for it, like Magliano, Martine Rose, or Grace Wales Bonner do.

But here, there’s no blood—only the dramatization of themes that deserve more depth.

Highlight: The weekend outfit that would be amazing if it were by Ralph Lauren.

22. Lemaire

It’s almost unsettling how the aesthetic of Lemaire—once intellectual and niche—has now become shockingly mainstream. The brand, designed by Christophe Lemaire and Sarah-Linh Tran, was one of the pioneers of a style once associated with Chelsea gallery owners. It has now found the perfect market in an audience tired of streetwear but eager to erase any signs of affiliation or identity.

There are a few problems here. First, radical minimalism has trickled down to Zara—via Officine Générale and Totême. That means there’s now an indistinguishable range of oversized, cement-gray cotton poplin shirts available at all price points. Second, there’s been no real evolution at Lemaire. The narrative has stayed almost exactly the same, even though its meaning has changed.

Today, people who dress like this are upper-middle-class types who don’t ask questions, don’t seek answers, and just want to feel socially accepted.

This is a rare case of a brand that is really just a style—with no other qualities. And it’s all great... until that style goes out of fashion.

Highlight: When everything is so minimal it becomes anonymous.