Harnessing Nature: The rise of bio-solutions in Europe

August 2025

In the face of mounting environmental challenges, some people in Europe are looking to nature for solutions, as well as inspiration. Advances in technology mean that biology and technology can be combined to create green industrial solutions, or bio-solutions.

Bio-solutions – i.e. innovative products and processes derived from natural organisms and ecological systems – are increasingly recognised as possible key to shifting towards a sustainable, competitive and resilient European economy. Recent studies highlight their economic potential and explain how they relate to – and differ from – other nature-based concepts currently being debated.

Nature’s many roles: clarifying the concepts

Nature plays multiple roles in our well-being and economic development, but the concepts used to describe these roles are not interchangeable. Bio-solutions, nature-based solutions, ecosystem services and the bioeconomy, to name but a few, each capture different aspects of our interaction with, dependence on and derivation of value from nature.

Bio-solutions, refer to the application of biological resources, principles, or organisms to develop new products or processes that serve societal needs. Examples include enzymes used in green chemistry, microbial treatments for wastewater, and plant-based materials for packaging. They typically involve innovation and market-ready deployment.

Nature-based solutions involve using or enhancing natural systems and processes to address societal challenges such as climate change, disaster risk, water management and urban resilience. Examples include restoring wetlands to reduce flood risk, planting urban forests to cool cities, and using green roofs for stormwater retention. While not always market-based, nature-based solutions often require coordinated governance and investment.

Ecosystem services are the benefits that people obtain from ecosystems. These include provisioning services (e.g. food and water), regulating services (e.g. climate control and disease prevention), cultural services (e.g. spiritual and recreational benefits), and supporting services (e.g. nutrient cycling). These are often public goods and difficult to commercialise.

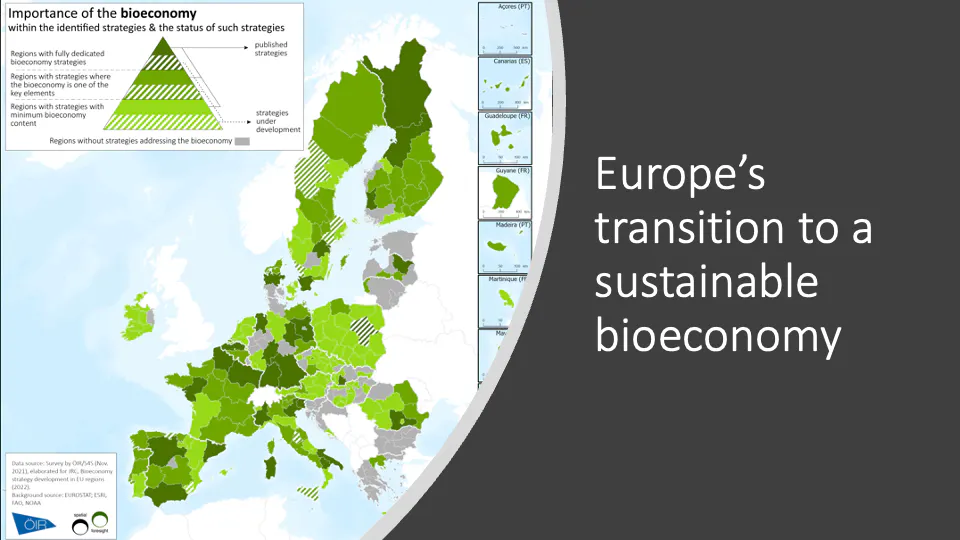

Bioeconomy is a broader economic model that integrates the sustainable use of biological resources across all sectors, from agriculture to industrial processes. The aim is to replace fossil-based inputs. This topic was also discussed in an earlier blog post (S'ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre). Bio-solutions are one of its innovative drivers.

The differences lie in orientation and scope. Ecosystem services emphasise the intrinsic and often non-market value of intact ecosystems. Nature-based solutions focus on leveraging or restoring these ecosystems to generate practical societal benefits, often through spatial planning or infrastructure. The bioeconomy frames a long-term economic transition that is grounded in biological materials and cycles. In contrast, bio-solutions are specific, applied innovations operating at the intersection of biology and technology. They are often designed to substitute harmful inputs, enhance efficiency or generate new value chains.

Recently, the concept of nature credits has also emerged in the debate. More about that further down.

A growing market with territorial potential

Bio-solutions are not only good for the environment; they are also becoming a significant economic force. According to a report published by the Bio-based Industries Consortium in June 2025, 'The Value of Biosolutions: Growth and Prosperity to 2035 (S'ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre)', the sector already contributes around EUR 60 billion in direct and indirect value to the EU economy, supporting 278 000 jobs across rural, urban and industrial regions. These figures are projected to nearly double by 2035, reaching EUR 118 billion and creating more than 543 000 jobs, with a particularly strong impact expected across various industries. From agriculture and chemicals to food and beverages and biofuels, bio-solutions are pivotal in driving job creation, innovation, and sustainability.

These developments have a very clear regional basis, extending beyond high-tech hubs and urban innovation districts. Many bio-solutions rely on regionally available biomass, local expertise, or distributed manufacturing systems. Bio-solutions emerge from context-specific conditions. As such, they offer decarbonisation potential and can contribute to territorial resilience. This makes them a natural addition to place-based development strategies and smart specialisation policies.

EU policy: from research to real-world deployment

The EU has long supported bio-solutions through its research and innovation programmes. Some examples include:

The EU Bioeconomy Strategy's longstanding emphasis on the sustainable use of biological resources.

The Farm to Fork Strategy sets ambitious targets to reduce the use of chemical pesticides, creating regulatory opportunities for biopesticides and microbial alternatives.

The Circular Economy Action Plan and the Sustainable Products Initiative aim to make renewable and bio-based materials mainstream in product design and procurement.

Under Horizon Europe, funding has supported research and innovation (R&I) on bio-based solutions, while the Circular Bio-based Europe Joint Undertaking (CBE JU) funds demonstration and scaling-up projects.

The focus is increasingly moving from early-stage innovation to deployment and market integration. The problem is no longer the lack of promising bio-based alternatives, but rather their uneven access to markets, standards and investment.

As the report 'The Value of Biosolutions: Growth and Prosperity to 2035 (S'ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre)' shows, many such products are blocked by regulatory inconsistencies or outdated classifications. Enzymes, for instance, are often still treated under chemical risk frameworks despite being biodegradable and safe by design. In agriculture, biopesticides face longer approval processes than their synthetic counterparts, which undermines their competitiveness at a time when the EU is trying to phase out chemical pesticides.

To address these issues, the report recommends a 'smart policy mix':

Modernise regulatory pathways to match the biological profile of these products.

Create clearer product standards and sustainability labels to foster market trust.

Foster public-private partnerships to scale-up infrastructure capacity for bio-solutions production in the EU, which will support SMEs and start-ups.

Support infrastructure for bio-manufacturing, particularly for SMEs and regional actors.

This is not just about fixing bottlenecks. It is about aligning the EU's industrial, environmental and cohesion ambitions – and doing so with a forward-looking view.

Nature credits and the financialisation of impact

More recently, the EU has also taken steps to facilitate the scaling up and market integration of nature-based approaches. One such initiative is the 2025 ’Roadmap towards Nature Credits (COM(2025) 374) (S'ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre)’, which introduces a framework for certifying and monetising nature-positive actions such as biodiversity restoration, improving soil health and increasing carbon sequestration.

The roadmap establishes the basis for a EU approach to nature credits, with the aim of scaling up biodiversity finance through voluntary, market-based tools. Although no regulatory steps have been proposed yet, the roadmap envisages a co-creation process involving pilot projects and stakeholder input to inform potential EU action after 2027.

In short, nature credits are envisaged as voluntary, high-integrity tools that reward stakeholders, such as farmers and landowners, for their role in delivering positive ecological outcomes. Unlike most bio-solutions, which involve product innovation, nature credits quantify ecological impact, thereby making restoration and conservation investable activities.

The ‘Roadmap towards Nature Credits (S'ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre)’ outlines a two-step system:

Certification of nature-positive outcomes (e.g. via improved ecosystem condition or function); and

issuance of credits that can be purchased by private actors, such as companies seeking to meet biodiversity targets or climate neutrality goals.

Unlike carbon credits, which focus on reducing emissions, nature credits cover a broader ecological footprint. Unlike subsidies or grants, they promise to channel private finance into ecosystem restoration, turning environmental care into an investable activity.

This may open intriguing opportunities for bio-solutions. For example, a microbial soil enhancer that improves nutrient retention and increases biodiversity could reduce the need for chemical fertilisers and generate certified ecosystem gains. This could enable farmers or landowners to generate dual value: one from the product and another from the credit it helps to unlock.

However, the credit model also raises questions:

Who defines what counts as 'nature-positive'?

How can we avoid greenwashing or displacement effects?

And will market-based instruments deliver the necessary scale and equity?

Looking ahead: lessons for regions and policy makers

With the EU preparing for the next financial period and a potential reimagining of green transition policies, it is time to recognise that bio-solutions offer more than just technical fixes. These solutions have the potential to create jobs, revitalise rural economies and contribute to Europe’s climate and biodiversity goals.

Key takeaways for regional and policy stakeholders:

Clarity of concepts matters. Conflating ecosystem services, nature-based solutions, bio-solutions, and the bio-economy can dilute their impact. Policies need to differentiate between the provision of public goods (e.g. pollination) and marketable innovations (e.g. pollinator-friendly seed treatments).

Territorial strategies should embrace bio-solutions. Smart specialisation, cluster initiatives and regional innovation platforms can help to integrate bio-solutions into local contexts.

Financial tools are evolving. Nature credits could complement cohesion and common agricultural instruments by providing performance-based finance for nature-enhancing innovation.

Demand needs to be nurtured. Beyond pilots and technical capacity, real-world uptake requires supportive procurement rules, awareness campaigns and incentives for buyers.

In summary, the future of bio-solutions lies not only in scientific laboratories, but also in policy frameworks, regional strategies and governance models that enable them to be scaled up. With the right support, they could become a defining feature of a Europe

by Kai Böhme

(S'ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre)

(S'ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre)